By Zack Fishman, Dec. 18, 2019 —

The locked office of the late climate scientist Wallace “Wally” Broecker displays a wooden ship’s wheel, mounted on a window-paneled wall behind his former desk. The wheel overlooks the forested campus of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, where Broecker conducted research for nearly 70 years. It originated from one of LDEO’s first vessels used for ocean chemistry testing in the 1960s, and the choice of its current home is no accident: The captain’s wheel is symbolic of Broecker’s leadership at the institution, says paleoclimatologist and LDEO professor Jerry McManus.

Broecker, who died in February at the age of 87, made significant contributions to the scientific understanding of the oceans, climate and climate change during his long academic career, mentoring several generations of students. Born in Oak Park in 1931 as the second of five children, he received his Ph.D. in geology at Columbia and became an assistant professor there in 1959. Since then, he pioneered the use of carbon isotopes and trace compounds to date and map the oceans, as well as introducing the concept of a “global conveyor” that connects the world’s oceans through heat-driven circulation. Broecker also popularized the phrase “global warming” in a 1975 paper and has been deemed the “grandfather of climate science” by many in the field.

More than 200 researchers and family members celebrated his legacy at the Wally Broecker Symposium in late October, with many of the world’s leading earth scientists in attendance. McManus led the organization of the three-day conference, which took place on the LDEO campus, an hour’s drive north of Columbia’s main campus in Manhattan. Dozens of Broecker’s former students and colleagues presented new research based on his findings, as well as heartfelt and entertaining stories about the late scientist.

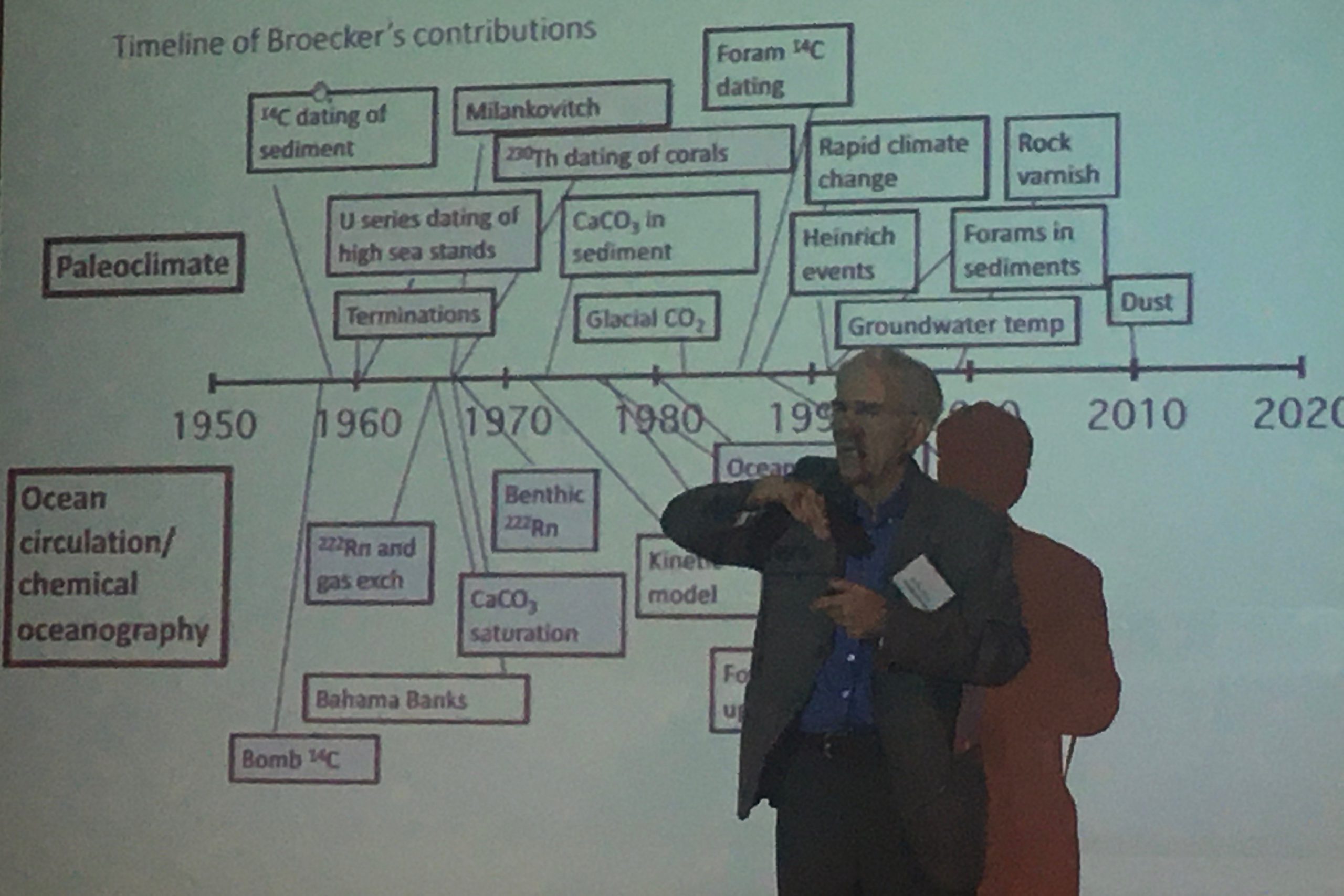

Princeton geoscientist Michael Bender opened the symposium with a summary of Broecker’s decades-long career, which he said spanned dozens of research topics and many ambitious experiments. Bender said Broecker first visited LDEO for a summer job in a lab and he learned about the new technology of radiocarbon dating, or measuring isotopes of carbon to determine the age of materials. Broecker’s supervisor was impressed enough to arrange the young scientist’s transfer to Columbia from Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, for his senior year and asked the 22-year-old to take over the lab.

An innovative Broecker would go on to use radiocarbon dating in 1958 to measure how glaciers affected the depth of a prehistoric lake in Utah. He also pioneered the use of tracking radioactive particles to study circulation in bodies of water, as he did in the 1980s when he poured radium into lakes in Ontario, Canada — with governmental permission — to follow its motion.

“I tried to look at Wally’s work as a whole, and the scope is just completely overwhelming,” said Bender, one of Broecker’s former students. “We were incredibly lucky to have the opportunity to be associated with this man and his science.”

Other researchers from numerous fields credited Broecker’s findings as foundational to their work. Geoscientist Jean Lynch-Stieglitz of the Georgia Institute of Technology said she “found Wally’s fingerprints all over” her research, as she used his model of the ocean “conveyor belt” to track how nutrients and heat circulated in the last 10,000 years. LDEO paleoclimatologist Dorothy Peteet shared the results of her and Broecker’s joint investigation into the causes and timing of glacier retreats during the last ice age.

Presenters also highlighted the scientist’s outspoken views on addressing climate change. Peter Schlosser, an earth scientist at Arizona State University, played a video clip of Broecker’s final address to the scientific community about necessary actions to limit global warming. From his hospital bed in 2018, Broecker said more drastic climate mitigation measures must be considered, such as capturing carbon dioxide from the air or injecting cooling aerosols into the atmosphere. The address was first played at the Planetary Management Symposium, held last year at Arizona State.

“If we are going to prevent the planet from warming up another couple degrees,” Broecker said, “we’re going to have to go to geoengineering.”

Praise of Broecker’s personal character pervaded the symposium with warm testimonies to his values and quirks. He was an “intellectual snow plow” who tackled problems with rigor and confidence, said Princeton geophysicist Daniel Sigman. His passion sometimes overflowed into what LDEO oceanographer Mark Cane called “strategic and effective” tantrums, often digging in his heels against administration and correcting guest speakers in his own class. Broecker was also a lifelong prankster, with stories of his tomfoolery tracing back to high school, when he rarely got caught. More recently, he had a staff member take his place during a video conference and mime the words Broecker was saying off-camera. (He didn’t get away with that one.)

“He had such a human heart,” McManus said, and fellow LDEO faculty member William Ryan called Broecker a “master of kindness.” Numerous attendees said he was an important influence in determining their career path as someone who often opened doors of opportunity. Ahbijit Sanyal, a director at Johnson & Johnson and another former student, said his teacher was “like a father” to him and once used his influence to help Sanyal’s wife immigrate to the U.S.

Yet more often, Broecker played down his status as a prolific researcher, and one scientist said he didn’t care about “personal wealth” or “glory.” He seemingly disliked his fame for popularizing the phrase “global warming” — he once offered his students $250 to find an example of its use before his landmark 1975 paper, though none were successful.

But Broecker paid a lot of attention to young scientists and their success. Encouragement and affirmation goes a long way for junior scientists, said Mayaan Yehudai, a Ph.D. student at LDEO and previously a teaching assistant for two of Broecker’s classes.

“When you’re a student, you don’t always know when you know that you’re qualified,” Yehudai said. “So, to have somebody like that tell me that I’m qualified or to believe in me is very, very meaningful.”

After the first full day of presentations, the visitors attended a ballroom dinner and listened to several heartfelt speeches from Broecker’s family and friends, including several senior members of LDEO. Filmmaker Anna Keyes presented a video centered around an interview with Broecker, her grandfather. His two younger sisters, Bonnie Chapin and Judy Revekop, told stories of growing up with a high-energy and caring Wally.

Broecker didn’t want a memorial, so the symposium was the largest gathering his family has attended in his memory, Revekop said. Nevertheless, she believes he would have appreciated the event.

“I’m sure he would love to be a little something sitting on a corner, watching and enjoying,” she said.

The dinner also featured an outpouring of musical talent. Geophysicist Richard Alley of Pennsylvania State University wrote and performed a song about his colleague’s career on a prerecorded video, drawing laughs from the attendees. Tom Chapin, a brother-in-law of Broecker and Grammy-winning folk singer, also played an original song about the late scientist’s research. His daughters, Abigail and Lily Chapin, later joined him to sing — this time, less about science and more on spiritual unity.

Broecker’s daughter Cynthia Kennedy, who attended the dinner and livestreamed the seminar, said the symposium was “fabulous” and praised the community of scientists it brought together.

“What they did for him was as much as he gave to them, because that’s what kept him going: their curious minds and their youth and their energy,” Kennedy said. “He fed on that, and that’s what made him who he was.”

Read more about Wally Broecker and his partnership with late philanthropist Gary Comer to launch a national initiative of climate research fellowships that Comer funded. The Comer Family Foundation continues to support the climate change research program.

Photo at top: Wallace Broecker in 2018 at Leeward Farms in Casper, Wyoming. (Jasmin Shah/Comer Family Foundation)