Featured Coverage

- January 29, 2021

- lbmeissner

PODCAST Global carbon dioxide emission dropped 7 percent worldwide due to a decrease in human activity after COVID-19 brought much of the world to a

- December 18, 2020

- Shivani Majmudar

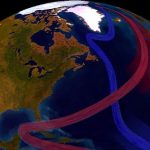

Amid this year’s global pandemic, the world is also fighting more frequent and severe hurricanes, larger wildfires and prolonged heat waves—indicative that climate change is

- December 18, 2020

- Grace Elizabeth Rodgers

In a race against climate change, Yuxin Zhou, 26, is among the next generation of climate scientists studying the Earth’s responses to rapidly rising temperatures,

- December 18, 2020

- Marisa Sloan

Despite the sci-fi name of this rare-earth element, neodymium is actually pretty common. The silvery metal is used in everything from cell phones and wind

Categories

Latest Articles

December 30, 2024

December 30, 2024

Contact Information

Abigail Foerstner, Managing Editor and Medill Associate Professor