By Kevin Stark –

Throngs of demonstrators frustrated with government inaction on climate change filled the streets of Manhattan in fall. They wore cardboard cutout life preservers that said “preserve our communities.” They carried a giant sunflower, nearly the width of a city street. Colorful signs, young and old, a cross-section of America.

And there was Yonig Goldsmith wearing a white robe like a prophet, but carrying a graph like a climate scientist. He is a climate scientist and the white robe was a lab robe.

“The scientists—there were not that many—but we all stood with signs that were posters of different plots [on graphs] showing what is happening,” Goldsmith said.

What role should science play in climate change advocacy?

This fall, Goldsmith and other scientists at the Comer Abrupt Climate Change Conference in southwestern Wisconsin grappled with this question. The conference is hosted by the Comer Family Foundation, which supports widespread climate research, and it brought together top climate scientists working from Antarctica to Greenland and everywhere in between.

The scientists agree that Earth is rapidly warming and that poses risks to human well being. But researchers do not agree on how to best take up the challenge of telling the climate change story. In emotion their responses range from optimistic to despondent, in strategy from advocacy to a focus on economic growth.

How do we talk about climate change so that people care even while they worry about making the rent? How do scientists communicate the threat of an abruptly warming planet to a public that often requires clarity, brevity, and certainty?

In December, world leaders will gather in Paris for the United Nations climate-change conference. Advocates are hopeful that the first global pact to limit greenhouse-gas emissions will be signed. Remember, in 1997 a framework was drawn up in Kyoto, Japan, to take a firm stand, but “the agreement failed on the international stage,” Jonathan Chait writes in New York magazine.

Goldsmith is a Columbia University doctoral candidate studying ancient lake levels in China. He believes that now that a global agreement is likely to be forged, scientists need to take an active roll in the advocacy debate. He is somewhat of an outlier among his colleagues.

To be clear, researchers should not be activists based on the premise of scientific objectivity, Goldsmith said. But researchers should not be on the sidelines either. For Goldsmith, scientists need to be there, holding evidence. Pointing to data. Stating the case. “CO2 is rising. The oceans are warming. The glaciers are melting with an exclamation mark,” Goldsmith said.

Is there collaboration in climate messaging within this community? Does anybody agree?

Action Agenda

Goldsmith and I spoke about the role of scientists in the policy debate at the conference, several months after the march in Manhattan. He was preparing to participate in another march the following week at Columbia University, where he is a doctoral candidate studying with climate pioneer Wally Broecker.

Broecker, a geochemist at Columbia University, coined the phrase global warming in the 1970s and became the “Grandfather of Climate Science.” He famously told the New York Times, “The climate system is an angry beast and we are poking at it with sticks.”

During the 1970s, believing that immediate action was needed to mitigate global warming, Broecker sent letters to senators, wrote papers, and generally “tried to advocate in this way—that is his avenue” Goldsmith said.

But for Goldsmith, letters and papers are no longer enough. Goldsmith says this to his veteran colleagues at the conference: you are the most “influential climate scientists in the world” and you have to “get up and talk about this.”

Broecker’s response (and the conversation) mirrors the greater debate within the science community. For Broecker, his role is as a scientist—not at all an activist—and to be credible he must remain objective and neutral, he says..

Goldsmith agrees that scientists need to be careful about discrediting their research, but he does see a need for a more active roll for researchers in the public debate. “Scientists are the ones that have to say, this is what what we work on, this is the logic, this is what we have. This is the evidence,” he says.

Researchers should focus on understanding the science. Activists should focus on divestment from fossil fuels, Goldsmith said. He points to the success of writer and environmentalist Bill McKibben, winner of the Right Livelihood prize in 2014 and founder of 350.org. McKibben organized the Manhattan march.

McKibben is leading an international movement to ‘divest,’ from the fossil fuel industry. He encourages organizations, universities, and others to withdraw financial investment from the oil and coal industry. Today, economists consider investing in the oil industry as a risk, in part, because of this advocacy (oil prices are dropping drastically because of over-supply which strengthens the argument for divestment).

“I very much believe in the economics approach because it makes sense to people,” Goldsmith said. “It is not this vague suffering of some whatever in some place in the world, which we cannot relate to.”

But only a handful of science researchers are actively engaged in the economics debate—Richard Alley of Penn State ranking among the most prominent. So, what does he think?

Alley said that communicating his fascination for science to a public audience was a “transition” and a “jolt,” and that policy is lagging behind the science. But he believes he found a message that will resonate with people: business.

Today, Alley is widely regarded as one of the best communicators of climate science. Alley, a glaciologist and geosciences professor at Penn State, wrote the book “Earth: The Operator’s Manuel,” the companion book to a widely popular PBS documentary (both were significantly more popular than the “Fate of Greenland”).

He also may be a perfect messenger as someone who is “right of center” and has “enjoyed working for an oil company and benefited from its largesse.” Alley believes the answer to the problem of how to engage with the public about climate change has the power of the free market behind the message.

He said that people will take action to reduce carbon emissions “because there is money to be made as much as ethically important things to do.”

It is not the case that doing the right things for future generations means “hurting ourselves now,” he said. He sees business opportunities and innovation where other see downsizing if we hope to reduce emissions.

The former vice president and author of “An Inconvenient Truth,” Al Gore is also advancing what has been called “sustainable capitalism” through Generation Investment Management, a company that “shifts the incentives of financial and business operations” to reduce damage to the environment caused by “unsustainable commercial excesses,” according to a recent article in The Atlantic.

Gore and Alley agree that including environmental and social impact on corporate activity can actually result in bullish gains in capital and that there is “money to be made,” (as Alley put it) and that returns can be better than just as good (according to Gore).

Gore has been able to prove that money can be made in sustainable energy investments, but there is no a guarantee that climate change will be solved on a policy level, or even that the renewable market will replace traditional oil and coal. As Bill Gates put it in a separate Atlantic article, renewables will be “uncertain compared with what’s tried-and-true and already operating at unbelievable scale.”

Even the message of the melting ice can be a tough sell.

Philip Conkling co-wrote “The Fate of Greenland: Lessons form Abrupt Climate Change” with Alley, Broecker, and University of Maine climate researcher George Denton. The book chronicled the melting ice sheet covering much of Greenland, the culmination of years of science and many voyages in the glacial North.

The book was supposed to “change the world, or at least make a little ripple,” Conkling said. But it sold 4,633 copies. “It was like, what a disappointment,” Conkling said.

Conkling is the founder of the Island Institute, a non-profit that advocates for the remote coastal communities off the coast of Maine and in other areas. He is a rare non-science presenter at the Comer conference.

He lectured on how to tell the climate story and began by saying, “I was going to subtitle this presentation 35 years of failure but I thought that would be a little grim.”

Still, the success of collaboration between communities and the Island Institute encourages him. His newest enterprise, Philip Conkling and Associates, is a consulting firm that guides the vision and planning of non-profits.

Islands aren’t the only places that need protection as the climate risks grow.

Hurting Ourselves Now

A few months ago, I was talking about sea-level rise and development in the San Francisco Bay Area on a local radio program. I had just published an investigative package with a local news organization that detailed $21 billion worth of current bayside development projects in an area that scientists say could be flooded by the end of the century as glaciers melt, pouring more water into the oceans.

The station took a call from a skeptical listener who said the research was full of “could be” statements and projections and wondered what about the research was news.

The caller and often apathetic policymakers are a problem for journalists and scientists who worry about what will happen if carbon emissions continue to climb and the planet continues to warm dramatically and quickly.

The biggest sticking point often for public engagement is the uncertainties that are inherent in climate modeling. Projections of sea-level rise – one of the key threats -fall in ranges. The projections are a product of highly complicated scientific models, and researchers can run different scenarios of action (and inaction) to mitigate carbon dioxide emissions.

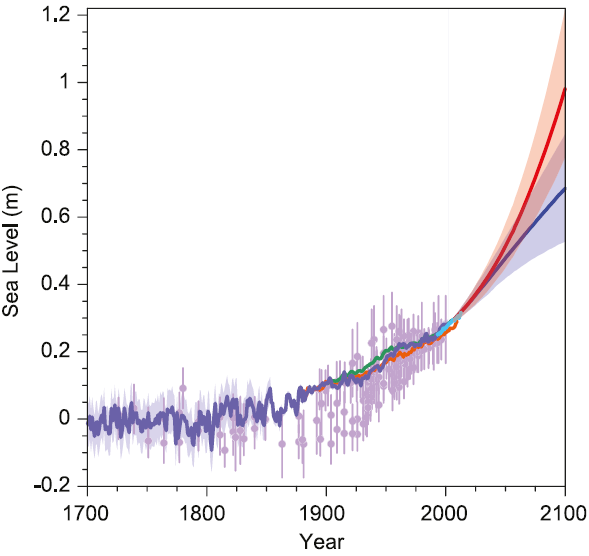

With the United Nations fifth assessment in 2013, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicted that sea levels could rise between 11 and 36 inches by the year 2100, depending on how aggressively carbon emissions are reduced.

The difference between the low and high projections could mean billions of dollars in adaptation planning for coastal communities. And that’s without even looking beyond this consensus figure to other, less conservative projections. The gap, reflecting the rate of melting of the vast polar ice sheets, often leaves policymakers scratching their heads.

Which is another way of saying, it leaves policymakers inactive.

The report I published with a team at the San Francisco Public Press found 27 bayfront megaprojects – including new headquarters of Facebook, LinkedIn, Google – all in low-lying areas that climate scientist say could flood by the end of the century.

While interviewing policymakers, the uncertainty came up a lot, mostly as an excuse for why no specific sea-level rise regulation on the books for business in the Bay Area.

“It may be unwise—and expensive—to require immediate measures to adapt to wide-ranging, highly uncertain sea-level rise projections further out in time,” wrote San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee in a memo to a civil grand jury convened before the investigative package ran. His administration has said that sea-level rise regulation needs to be written with nuance to adapt to changing science.

Alley said that inaction because of uncertainty is short-sighted, and compared it to not buying car insurance just because there’s no certainty we will have an accident.

“The uncertainties actually motivate doing more,” Alley said. “You do not know whether or not you will be run over by a semi on the way to work, but you should buy a safe car, buckle your seatbelt and not drink while you are driving.”

Alley said scientists need to “care deeply and passionately about how things work,” but communicating this message to the public is a difficult challenge—and one that a new generation of researchers is leaning into by taking journalism classes and putting off research to collaborate with science reporters.

While the scientific community is in consensus that badly needed mitigation of the rate of carbon dioxide being released into the atmosphere is needed to slow the current rapid period of global warming, not all scientist agree that financial markets will solve the problem.

Guleed Ali, a graduate student at the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Columbia University, is skeptical of the marketsplace solving the problem.

“We are here today because of business” pushing fossil fuel use, he said. He sees winning support from other perspectives.

Ali researches the geomorphic record of Mono Lake, which is a large, shallow saline soda lake in the Eastern Sierra of California, and he often speaks to the local community about his work.

Through trial and error—or “talk and blab” as he put it—Ali found that people engage more with images, or in his case, with art. Ali produces graphic images that explain the dense science. “That is the most straightforward way to penetrate that initial wall,” Ali said. “Art is something that is engaging. It is disarming.”

Science is a world of charts, graphs, data points, but Ali sees the world differently. “For someone like me, pictures are so much simpler,” he said. “They give life to these inanimate things that we write about.”

Ali said the route to solving the issue of global warming is through the hearts and minds of the public. People need to “see with their own eyes,” he said.

“If you see steam coming out of the bowl you know that the bowl is hot,” Guleed said. “It’s steam.”

The problem is that the majority of the public in the United States is disconnected from the changes that are taking place in the Earth’s climate. He said it is “abundantly clear” for those communities—“farmers and pastorals”—that are connected to the earth in a direct way.

The question for some of Ali’s colleagues is this: can engaging with people on an emotional level—providing steam-from-the-bowl evidence that the world is rapidly warming—move the public fast enough to mitigate warming?

The “ultimate objective” of the International Panel on Climate Change to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations at a level that would prevent “dangerous anthropogenic interference” with the climate system—read: keep the world climate from being so screwy that society cannot grow food or live in coastal communities.

This temperature level is 2 degrees Celsius higher than pre-industrial levels. Today, we have already reached half that level of temperature rise and the other half is already spooled into the atmosphere.

If 2 degrees does not seem like a big deal—temperatures can vary 20 or 30 degrees in any given day. But it is important to to understand that the figure represents global average. If the global average temperature rises above the 2-degree mark, atmospheric climate will be disrupted. The world could see severe drought, less rain but more severe storms, and it will be a challenge to grow food to feed the world’s population.

It is clear from conversations at the Comer conference that every one agrees on one thing – the story of climate change needs to be told. All of the researchers I spoke with are doing this in some way. But, it was also clear that the science community doesn’t agree on how to tell the story. They are still debating, proposing and challenging – which they do in their science as well.

But they all keep trying to tell the story. And they all seemed to have hope.

“People will get there,” Ali said. “We are doing this for that reason.”